Build your own static site generator (because why not?)

Jun 1, 2019If you're anything like me and struggle to blog consistently, despite believing in its instrinsic value, then I'm sorry I have no good advice for you.

However, perhaps building your own blogging platform from scratch (or, indeed, writing the guide on how it's done) could give you the motivation you so desperately need.

In this guide I'll walk you through the steps of building your own static site generator (SSG) from start to finish using the following components:

- Node.js - minimum version 12.x ⚠️

- Markdown - a sensible markup language to write posts in.

- Netlify - a superb static site host provider.

Or if you'd like, you can skip straight to the GitHub repo for this guide.

Why build your own?

To address the 🐘 in the room; out of the almost endless list of ready-built, static site generators available, why would anyone choose to build their own?

While I do recommend using a battle-tested SSG for official business, their inherent complexities can be overkill for the general hobbyist's need. Building a static-site generator is a surprisingly simple, fun exercise that, at the very least, will leave you with a greater understanding of your chosen programming language's file system/IO library.

Overview

These are the core concepts outlined in this guide:

- Create HTML templates

- Create a new post

- Retrieve the posts

- Convert Markdown to HTML

- Generate HTML files

- Initialize the project

- Deploy to Netlify

- Final thoughts

Folder structure

.

├── index.js

├── posts/

│ ├── hello-world.md

├── public/

│ ├── hello-world.html

│ └── index.html

└── templates/

├── base.njk

├── post.njk

└── index.njk

index.jscontains the application logic.postsdirectory contains the blog posts written in Markdown.publicdirectory contains the generated HTML files. Everything in this directory will be publicly-accessible, so it's a good place to store assets like images and CSS too.templatesdirectory contains the templates used to generate the HTML files.

Create HTML templates

The static site generator is responsible for generating HTML pages from raw content. HTML templates provide the structure and appearance that the markup in the generated file adheres to. A template engine is used to define the templates and generate the files.

We're using Mozilla's Nunjucks, due to its syntax being the most similar to HTML, but other options include EJS, Handlebars or Pug (a personal favourite).

Create the templates directory to start.

# Create a directory for templates

mkdir -p templates

Base template

The parent template includes a top-level structure, common to all generated files. It contains two modular blocks, for the head and body, that can be edited from any child templates.

# Create the template file

touch templates/base.njk

Save the following content inside the file you created:

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

{% block header %}

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta description="{{ description | default('Build your own static site generator') }}">

<title>{{ title | default('Blog')}}</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="//cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/modern-normalize/0.5.0/modern-normalize.min.css">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="//cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/github-markdown-css/3.0.1/github-markdown.min.css">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="//cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/highlight.js/9.15.6/styles/default.min.css">

{% endblock %}

</head>

<body>

{% block body %}{% endblock %}

</body>

</html>

The default filter is used to create a site title and description in the absence of one, while the linked stylesheets add some basic styling to the rendered HTML, making it more readable.

Post template

A child template of the base template, the post template renders the markup for the blog post content within the parent's body block.

# Create the template file

touch templates/post.njk

Save the following content inside the file you created:

{% extends "./base.njk" %}

{% block body %}

<article>

<header>

<h1>{{ title }}</h1>

</header>

<div class="markdown-body">

{{ body | safe }}

</div>

</article>

<script src="//cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/highlight.js/9.15.6/highlight.min.js"></script>

<script>window.hljs.initHighlightingOnLoad();</script>

{% endblock %}

The body variable contains the post content in pure HTML, so the

safe filter

is needed to prevent the template engine from escaping the HTML tags.

The scripts towards the bottom initialize highlight.js

to provide syntax highlighting in code blocks. The class .markdown-body is required

to allow this to work.

Index template

Another child template of the base template, the index template contains a list of links to posts that were created by the generator. The file generated by this template will serve as the site's homepage.

# Create the template file

touch templates/index.njk

Save the following content inside the file you created:

{% extends "./base.njk" %}

{% block body %}

<section>

<header>

<h1>Blog</h1>

</header>

<ol>

{% for post in posts %}

<li>

<a href="{{ post.slug }}">{{ post.title }}</a>

</li>

{% endfor %}

</ol>

<section>

{% endblock %}

Create a new post

All posts are saved inside a posts directory, so start by creating that.

mkdir -p posts

Markdown

Like most static site generators, our posts will be written in Markdown. It's a minimalistic markup language that's well-suited to writing articles and easily converts to HTML. I recommend reading this guide to become more familiar with it.

Front matter

Given that static site generators don't have databases the way traditional blogging platforms do, the post metadata (title, author, publish date, etc.) is stored in the post itself. The top part of the file contains a block of YAML config representing this data.

---

title: "Hello, world!"

author: "Me"

date: "2019-06-01"

---

This is called the front matter, an idea shamelessly borrowed from Jekyll.

Post metadata is consumed by the template engine to populate relevant HTML tags, and also by the generator to manage the posts.

Choosing a file name

The file name you save your post with is the same file name used to generate the HTML file, so it's important to choose one that is URL-friendly. The standard process is to slugify the post title.

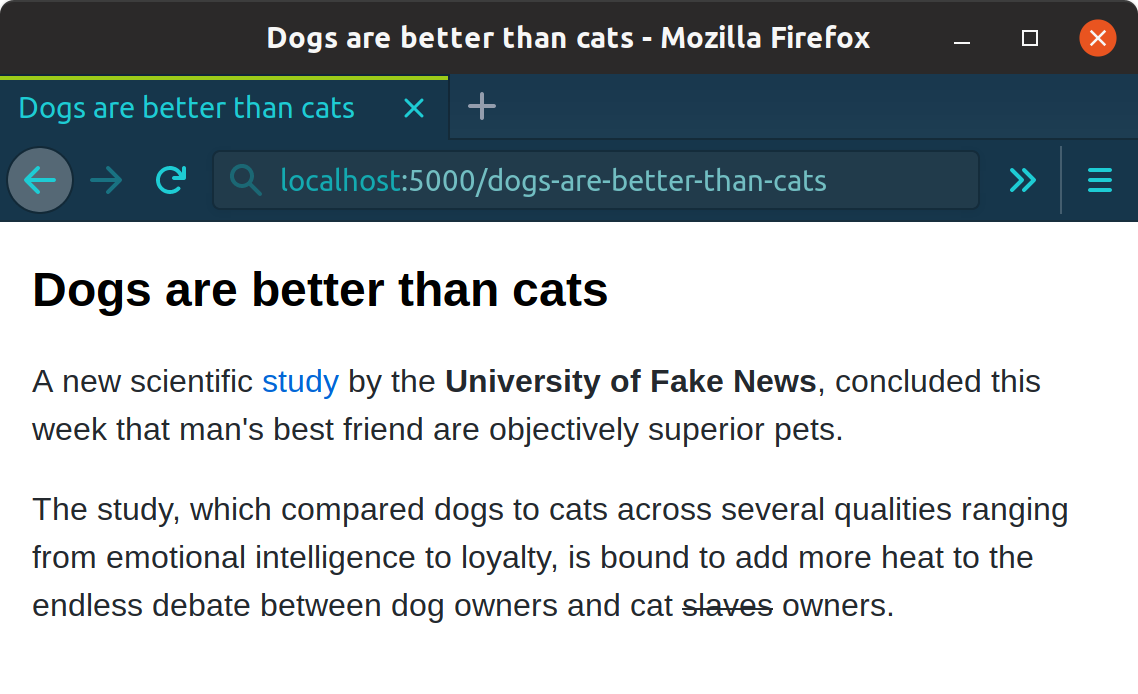

For example, save the following file in the posts directory as

dogs-are-better-than-cats.md:

---

title: "Dogs are better than cats"

description: "Study concludes that dogs make better pets than cats."

date: "2019-06-01"

public: true

---

A new scientific [study](https://example.com/science.php) by the

**University of Fake News**, concluded this week that man's best friend

are objectively superior pets.

The study, which compared dogs to cats across several qualities ranging from

emotional intelligence to loyalty, is bound to add more heat to the endless

debate between dog owners and cat ~~slaves~~ owners.

⚠️ Remember to use this post template for any subsequent posts that you make.

Retrieve the posts

To retrieve the Markdown files in the posts directory, we need to first assemble

a list of all the files in the directory, and then read the contents of each

file in turn, skipping over any sub-directories, or files that don't match an

.md extension.

The standard File System module in Node.js makes working with files easy. We can use it to create a generic method to list all files in a directory that match a certain file extension:

const fs = require('fs').promises;

/**

* getFiles returns a list of all files in a directory path {dirPath}

* that match a given file extension {fileExt} (optional).

*/

const getFiles = async (dirPath, fileExt = '') => {

// List all the entries in the directory.

const dirents = await fs.readdir(dirPath, { withFileTypes: true });

return (

dirents

// Omit any sub-directories.

.filter(dirent => dirent.isFile())

// Ensure the file extension matches a given extension (optional).

.filter(dirent =>

fileExt.length ? dirent.name.toLowerCase().endsWith(fileExt) : true

)

// Return a list of file names.

.map(dirent => dirent.name)

);

};

We used the fs.promises API to provide an alternate set of methods that

return Promises rather than using callbacks.

The withFileTypes option provided to fs.readdir makes it return a list of

fs.Dirents objects instead

of strings. These objects contain useful file validation methods based on the

data provided by libuv (the low-level C library that

Node.js relies on for file system operations).

Still, the validation methods do have limitations, so we have to manually check the file extension matches.

Get all posts in directory

Using the generic getFiles() method, we can create a posts retrieval method,

responsible for reading all the files in the posts directory, and returning a

list of post objects after parsing the file content(s).

const fs = require('fs').promises;

const path = require('path');

/**

* getPosts lists and reads all the Markdown files in the posts directory,

* returning a list of post objects after parsing the file contents.

*/

const getPosts = async dirPath => {

// Get a list of all Markdown files in the directory.

const fileNames = await getFiles(dirPath, '.md');

// Create a list of files to read.

const filesToRead = fileNames.map(fileName =>

fs.readFile(path.resolve(dirPath, fileName), 'utf-8')

);

// Asynchronously read all the file contents.

const fileData = await Promise.all(filesToRead);

return fileNames.map((fileName, i) => parsePost(fileName, fileData[i]));

};

In the next step, we'll create the parsePost() method to parse the file content

and transform it to a post object.

Parse the post content

We can create a method to transform the raw file content into a nicer format, specifically a post object that resembles:

{

"title": "Dogs are better than cats.",

"description": "Study concludes that dogs make better pets than cats.",

"slug": "dogs-are-better-than-cats",

"date": "2019-06-01",

"public": true,

"body": "A new scientific [study](https://example.com/science.php)"

}

Thankfully, we don't have to manually parse the file data to separate the front matter from the post content. We can rely on the front-matter package from NPM to do the heavy lifting for us.

const path = require('path');

const frontMatter = require('front-matter');

/**

* parsePost consumes the file name and file content and returns a post

* object with separate front matter (meta), post body and slug.

*/

const parsePost = (fileName, fileData) => {

// Strip the extension from the file name to get a slug.

const slug = path.basename(fileName, '.md');

// Split the file content into the front matter (attributes) and post body.

const { attributes, body } = frontMatter(fileData);

return { ...attributes, body, slug };

};

The post's front matter will be converted from YAML to an object named attributes, which we destructure alongside the body and slug into a new object.

Convert Markdown to HTML

Since we plan to write our posts in Markdown, we need a method that consumes Markdown text and converts it to HTML using a compiler.

The NPM package ecosystem being as extensive as it is, offers several compilers. The lines between these libraries can often be blurry, making it an arduous task in itself to choose the right one. Ultimately, trial and error remains the best approach to figuring out which one to use.

Based on my findings, I chose remark.js because it's pluggable, seems actively maintained, and has shown a positive growth trend 📈.

const remark = require('remark');

const remarkHTML = require('remark-html');

const remarkSlug = require('remark-slug');

const remarkHighlight = require('remark-highlight.js');

/**

* markdownToHTML converts Markdown text to HTML.

* Adds links to headings, and code syntax highlighting.

*/

const markdownToHTML = text =>

new Promise((resolve, reject) =>

remark()

.use(remarkHTML)

.use(remarkSlug)

.use(remarkHighlight)

.process(text, (err, file) =>

err ? reject(err) : resolve(file.contents)

)

);

This method is wrapped in a Promise to avoid the awkward callback-style API.

Remark plugins

Remark has a rich plugin ecosystem to add additional features to the parser. This guide uses the absolute minimum set that a tech blog would require, but feel free to experiment with others.

- remark-html - converts Markdown to HTML.

- remark-slug - creates linkable IDs for headings.

- remark-highlight.js - adds code syntax highlighting.

Generate HTML files

We need to create two methods; one for generating the files for blog posts, and the other to generate the index page.

Both methods will save the generated files in the public directory, so to avoid any errors, ensure that the directory exists:

# create public directory

mkdir -p public

The methods will also need a way to retrieve their associated Nunjuck HTML templates, so we can also create a helper method to resolve template file paths.

const path = require('path');

// getTemplatePath creates a file path to an HTML template file.

const getTemplatePath = name =>

path.resolve(__dirname, 'templates', path.format({ name, ext: '.njk' }));

Generate post files

The following method generates the HTML file for a blog post and saves it to the

public directory. It consumes the post object created by the parsePost() method,

and returns it successfully at the end.

const fs = require('fs').promises;

const path = require('path');

const nunjucks = require('nunjucks');

// Store a reference path to the destination directory.

const publicDirPath = path.resolve(__dirname, 'public');

/**

* createPostFile generates a new HTML page from a template and saves the file.

* It also converts the post body from Markdown to HTML.

*/

const createPostFile = async post => {

// Use the template engine to generate the file content.

const fileData = nunjucks.render(getTemplatePath('post'), {

...post,

// Convert Markdown to HTML.

body: await markdownToHTML(post.body)

});

// Combine the slug and file extension to create a file name.

const fileName = path.format({ name: post.slug, ext: '.html' });

// Create a file path in the destination directory.

const filePath = path.resolve(publicDirPath, fileName);

// Save the file in the desired location.

await fs.writeFile(filePath, fileData, 'utf-8');

return post;

};

Generate index file

The following method consumes the list of post objects to be generated, and

creates the HTML file for the index page, saving it in the public directory

as index.html.

const fs = require('fs').promises;

const path = require('path');

// Store a reference path to the destination directory.

const publicDirPath = path.resolve(__dirname, 'public');

/**

* createIndexFile generates an index file with a list of blog posts.

*/

const createIndexFile = async posts => {

// Use the template engine to generate the file content.

const fileData = nunjucks.render(getTemplatePath('index'), { posts });

// Create a file path in the destination directory.

const filePath = path.resolve(publicDirPath, 'index.html');

// Save the file in the desired location.

await fs.writeFile(filePath, fileData, 'utf-8');

};

Remove existing files

Each time we execute the generator, we need to first remove any existing HTML files from the public directory, so that it contains a fresh batch of generated files, and not any leftovers from a previous build session.

This absolute control over the public directory files allows us to make posts private once they are already set public.

We can re-use the getFiles() method to construct a generic method to empty

a directory by deleting any files that match a file extension.

const fs = require('fs').promises;

const path = require('path');

// removeFiles deletes all files in a directory that match a file extension.

const removeFiles = async (dirPath, fileExt) => {

// Get a list of all files in the directory.

const fileNames = await getFiles(dirPath, fileExt);

// Create a list of files to remove.

const filesToRemove = fileNames.map(fileName =>

fs.unlink(path.resolve(dirPath, fileName))

);

return Promise.all(filesToRemove);

};

We can use this later like so:

await removeFiles('/path/to/public/directory', '.html');

Initialize the project

The last few steps remaining before we can finalize the codebase include creating a method to run the generator, and initializing the project and installing dependencies.

We can also create a script to set up a local web server on our machines, allowing us to preview the site before making it public.

Run the generator

Create a build method that runs the generator in its entireity, glueing together all of the other methods that we created in this guide.

const fs = require('fs').promises;

const path = require('path');

// Store a reference to the source directory.

const postsDirPath = path.resolve(__dirname, 'posts');

// Store a reference path to the destination directory.

const publicDirPath = path.resolve(__dirname, 'public');

// build runs the static site generator.

const build = async () => {

// Ensure the public directory exists.

await fs.mkdir(publicDirPath, { recursive: true });

// Delete any previously-generated HTML files in the public directory.

await removeFiles(publicDirPath, '.html');

// Get all the Markdown files in the posts directory.

const posts = await getPosts(postsDirPath);

// Generate pages for all posts that are public.

const postsToCreate = posts

.filter(post => Boolean(post.public))

.map(post => createPostFile(post));

const createdPosts = await Promise.all(postsToCreate);

// Generate a page with a list of posts.

await createIndexFile(

// Sort created posts by publish date (newest first).

createdPosts.sort((a, b) => new Date(b.date) - new Date(a.date))

);

return createdPosts;

};

If the public directory is absent, for whatever reason, the generator will throw an error while attempting to save a file inside of it. Therefore, it's a good practice to pre-emptively ensure the directory exists (and is empty) at the start.

The list of posts that have been generated are sorted by date and injected as a dependency to the method that creates the index page. This allows the index template to list the posts in chronological order.

Any errors the generator produces downstream will bubble up to this build method, where we can catch them and log them to the console as follows:

build()

.then(created =>

console.log(`Build successful. Generated ${created.length} post(s).`)

)

.catch(err => console.error(err));

Create the index.js file

# create index file

touch index.js

Save the following content in the project's root directory in a file called

index.js. This is the final file that combines all of the other methods that

we covered in this guide.

const fs = require('fs').promises;

const path = require('path');

const frontMatter = require('front-matter');

const remark = require('remark');

const remarkHTML = require('remark-html');

const remarkSlug = require('remark-slug');

const remarkHighlight = require('remark-highlight.js');

const nunjucks = require('nunjucks');

// Store a reference to the source directory.

const postsDirPath = path.resolve(__dirname, 'posts');

// Store a reference path to the destination directory.

const publicDirPath = path.resolve(__dirname, 'public');

/**

* getFiles returns a list of all files in a directory path {dirPath}

* that match a given file extension {fileExt} (optional).

*/

const getFiles = async (dirPath, fileExt = '') => {

// List all the entries in the directory.

const dirents = await fs.readdir(dirPath, { withFileTypes: true });

return (

dirents

// Omit any sub-directories.

.filter(dirent => dirent.isFile())

// Ensure the file extension matches a given extension (optional).

.filter(dirent =>

fileExt.length ? dirent.name.toLowerCase().endsWith(fileExt) : true

)

// Return a list of file names.

.map(dirent => dirent.name)

);

};

// removeFiles deletes all files in a directory that match a file extension.

const removeFiles = async (dirPath, fileExt) => {

// Get a list of all files in the directory.

const fileNames = await getFiles(dirPath, fileExt);

// Create a list of files to remove.

const filesToRemove = fileNames.map(fileName =>

fs.unlink(path.resolve(dirPath, fileName))

);

return Promise.all(filesToRemove);

};

/**

* parsePost consumes the file name and file content and returns a post

* object with separate front matter (meta), post body and slug.

*/

const parsePost = (fileName, fileData) => {

// Strip the extension from the file name to get a slug.

const slug = path.basename(fileName, '.md');

// Split the file content into the front matter (attributes) and post body.

const { attributes, body } = frontMatter(fileData);

return { ...attributes, body, slug };

};

/**

* getPosts lists and reads all the Markdown files in the posts directory,

* returning a list of post objects after parsing the file contents.

*/

const getPosts = async dirPath => {

// Get a list of all Markdown files in the directory.

const fileNames = await getFiles(dirPath, '.md');

// Create a list of files to read.

const filesToRead = fileNames.map(fileName =>

fs.readFile(path.resolve(dirPath, fileName), 'utf-8')

);

// Asynchronously read all the file contents.

const fileData = await Promise.all(filesToRead);

return fileNames.map((fileName, i) => parsePost(fileName, fileData[i]));

};

/**

* markdownToHTML converts Markdown text to HTML.

* Adds links to headings, and code syntax highlighting.

*/

const markdownToHTML = text =>

new Promise((resolve, reject) =>

remark()

.use(remarkHTML)

.use(remarkSlug)

.use(remarkHighlight)

.process(text, (err, file) =>

err ? reject(err) : resolve(file.contents)

)

);

// getTemplatePath creates a file path to an HTML template file.

const getTemplatePath = name =>

path.resolve(__dirname, 'templates', path.format({ name, ext: '.njk' }));

/**

* createPostFile generates a new HTML page from a template and saves the file.

* It also converts the post body from Markdown to HTML.

*/

const createPostFile = async post => {

// Use the template engine to generate the file content.

const fileData = nunjucks.render(getTemplatePath('post'), {

...post,

// Convert Markdown to HTML.

body: await markdownToHTML(post.body)

});

// Combine the slug and file extension to create a file name.

const fileName = path.format({ name: post.slug, ext: '.html' });

// Create a file path in the destination directory.

const filePath = path.resolve(publicDirPath, fileName);

// Save the file in the desired location.

await fs.writeFile(filePath, fileData, 'utf-8');

return post;

};

/**

* createIndexFile generates an index file with a list of blog posts.

*/

const createIndexFile = async posts => {

// Use the template engine to generate the file content.

const fileData = nunjucks.render(getTemplatePath('index'), { posts });

// Create a file path in the destination directory.

const filePath = path.resolve(publicDirPath, 'index.html');

// Save the file in the desired location.

await fs.writeFile(filePath, fileData, 'utf-8');

};

// build runs the static site generator.

const build = async () => {

// Ensure the public directory exists.

await fs.mkdir(publicDirPath, { recursive: true });

// Delete any previously-generated HTML files in the public directory.

await removeFiles(publicDirPath, '.html');

// Get all the Markdown files in the posts directory.

const posts = await getPosts(postsDirPath);

// Generate pages for all posts that are public.

const postsToCreate = posts

.filter(post => Boolean(post.public))

.map(post => createPostFile(post));

const createdPosts = await Promise.all(postsToCreate);

// Generate a page with a list of posts.

await createIndexFile(

// Sort created posts by publish date (newest first).

createdPosts.sort((a, b) => new Date(b.date) - new Date(a.date))

);

return createdPosts;

};

build()

.then(created =>

console.log(`Build successful. Generated ${created.length} post(s).`)

)

.catch(err => console.error(err));

Install project dependencies

First create a new Node.js project with NPM, following the steps in the console to initialize the project:

npm init

Install the packages from NPM that this static site generator relies on:

npm install front-matter \

remark \

remark-html \

remark-slug \

remark-highlight.js \

nunjucks

Development tools

To make development easier, we can create a local web server to view our blog. The package serve from NPM is a great tool that has mimics our desired host (Netlify) quite well, so install it to development dependencies:

npm install --save-dev serve

We can run the generator through the npm command using NPM scripts. We need

one command to run the generator, and another to run our local development

server.

Add this block to your package.json:

"scripts": {

"build": "node .",

"start": "serve ./public"

}

Now you can run the above commands in the following way:

npm run build- Run the generatornpm start- Start the local web server

If you run the build command, then the start command, you should be able to point your browser to localhost:5000 and see the blog post you created!

Deploy to Netlify

Push to GitHub

The process of pushing the code to a repository on GitHub is tangential to this post, but the vague steps are as follows:

Connect to Netlify

TODO

Final thoughts

By using some native Node.js modules and packages from NPM, we were able to create a minimal static site generator. In the process we learnt a bit about how these generators work.

The code for this guide is available to view/fork in this GitHub repo.